China Elderly Emotional Companionship and Entertainment Learning Product Consumption Survey Report

- NXLongevity

- Aug 9, 2025

- 24 min read

Background Overview

China has entered an aging society. The seventh national census shows that the population aged 60 and above has reached 264 million, accounting for 18.7% [1]; by the end of 2024, this group is approximately 310 million, representing 22% of the total population [2]. With the widespread adoption of smartphones and the internet, the scale of elderly internet users has rapidly expanded. By the end of 2023, netizens aged 50 and above reached 350 million, accounting for 32.5% of the national netizen population [3]. Notably, elderly internet users spend significant time online—51% of middle-aged and elderly users spend over 4 hours online daily, surpassing the national average of 3.7 hours [4][5]. This silver-haired generation, with both time and financial resources, is actively embracing digital life, becoming an emerging force in online consumption and learning [6][7].

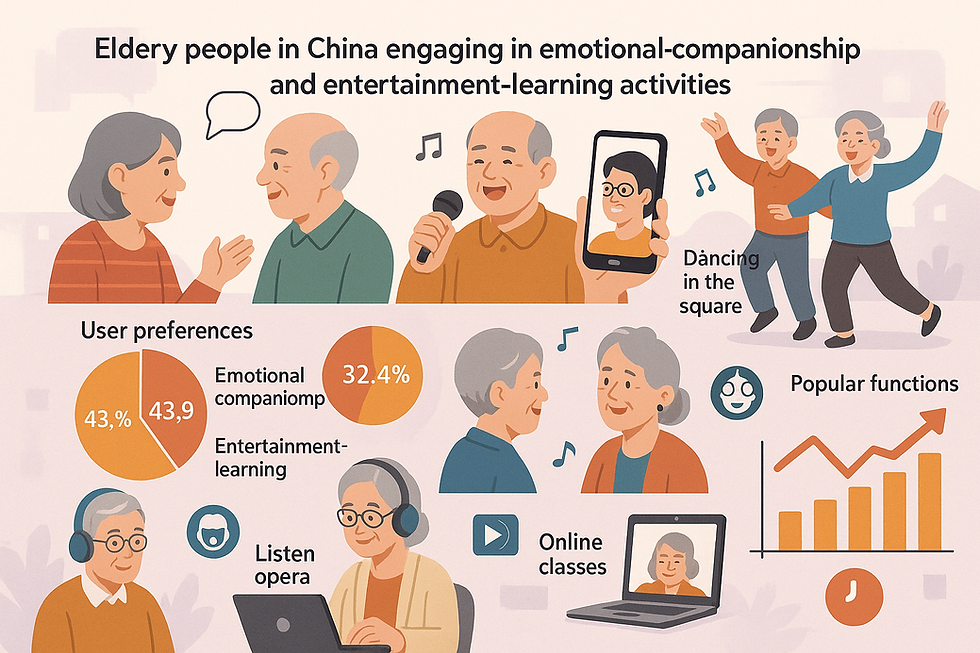

This report focuses on “community-active” elderly (those living at home but active in community social interactions) and “institutional care” residents (elderly living in nursing homes or similar facilities), surveying their consumption willingness, interest points, and preference data for two types of products:

Emotional Companionship Products: These provide emotional comfort, companionship through conversation, singing, or video calls, aimed at alleviating emotional loneliness among the elderly, such as intelligent companion robots, smart speakers/screens, and remote video call devices.

Entertainment and Learning Products: These cater to the entertainment and learning needs of the elderly, such as square dance apps, opera music devices or software, and online elderly education platforms.

The survey focuses on: the proactive interests and emotional motivations of elderly users, real market usage feedback (usage rates, typical usage periods, repurchase or recommendation behavior), typical functional entry points and service scenarios, and the true psychological reasons for elderly acceptance or rejection of these products (e.g., dignity, autonomy, social willingness). Where possible, differences across age groups, city tiers, and types of care institutions are also highlighted. The following sections provide an in-depth analysis of the two product categories.

Emotional Companionship Products: Consumption Willingness and Usage

User Needs and Interest Motivations

With the increasing aging population and the prevalence of empty-nest households, many elderly face a lack of emotional companionship. According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the proportion of empty-nest elderly (living alone or only with a spouse) exceeds 50%, reaching over 70% in some large cities and rural areas [8]. Reduced social interactions post-retirement, children living far away, and concerns about illness and aging make loneliness a common emotional issue among the elderly [9][10]. Companionship has thus become one of their essential needs [11]. Specifically, there are two main motivational factors:

Emotional Comfort for Loneliness/Emptiness: Due to prolonged lack of family companionship, empty-nest and solitary elderly have abundant leisure time but limited social activities, leading to loneliness that affects mental health [8][12]. Surveys show that about 15% of people over 60 suffer from depression, with rates as high as 50%+ when accompanied by physical ailments [13]. Moderate companionship is considered a “remedy” for preventing and alleviating elderly depression and cognitive disorders, providing emotional comfort [14]. Thus, many elderly yearn to express themselves and connect, creating a demand for emotional companionship.

Psychological Need for Safety and Care: High-age or physically declining elderly, especially those with mild disabilities or mobility issues, find it difficult to engage in frequent social activities and desire a “companion” to pay attention to them, reducing feelings of isolation [15][16]. They wish to avoid burdening their children while maintaining some autonomy, yet also want access to help in emergencies. Thus, some intelligent companionship devices with monitoring and emergency call functions can meet the elderly’s need for a sense of safety [17]. Emotional companionship products target this need for emotional care, alleviating loneliness through interactive chats, singing, or other means. For example, some companies have developed bionic pet robots with plush exteriors and touch feedback to provide comfort, making solitary elderly feel accompanied by a “little pet” [18][17].

Overall, “emotional companionship” touches the deep emotional motivations of the elderly: the desire for care, reducing loneliness, maintaining mental joy, and preserving dignity. As industry insiders note, the core of companionship is to make the elderly feel unisolated from the world [19]—even a responsive robotic companion can, to some extent, be better than an empty room.

Market Feedback and Usage

Market feedback shows that elderly companionship products are still in their early stages. Despite strong demand, the penetration rate of true emotional companionship products remains low, primarily entering elderly lives through gifting or institutional provisioning. According to Founder Securities, the penetration rate of intelligent robots in the elderly care sector has been increasing, with the market size of smart elderly care robots in China reaching about 25 billion yuan in 2023. By 2030, the penetration rate of emotional companionship robots is expected to reach around 5% [20]. This indicates that the proportion of individual households owning companionship robots is currently low, but the potential market is vast.

In terms of usage, some regions have begun trials. For instance, Liangshan County in Shandong Province installed 305 smart voice companionship devices, such as Baidu Smart Screens, in 13 nursing homes across the county [21]. These devices have been well-received by the elderly: at the nursing home in Shouzhangji Town, elderly residents are “busy listening to operas and making video calls,” showing improved mental states [22]. One elderly resident surnamed Sun excitedly demonstrated, “This Baidu Smart Screen is a treasure. It can play songs, operas, movies, and make video calls with family—very convenient” [22]. In institutional care settings, smart companionship screens meet the elderly’s needs for entertainment and family connection, with typical usage periods including daytime leisure for watching operas and evening video calls with family [22]. These products enrich the daily lives of nursing home residents, with directors noting, “A small screen makes elderly life richer and more convenient, while also monitoring health, reassuring families” [22].

However, in the home market, the sustained usage and repurchase rates of emotional companionship products face challenges. A survey on companionship robots found that while many elderly initially find robots novel and interesting, the “freshness” often fades. A Beijing Normal University study revealed that 78% of users experienced “electronic pet fatigue” after less than six months, feeling that the robots’ monotonous responses failed to build genuine emotional connections [23]. With an average price of over 10,000 yuan, robots that are neglected within six months struggle to sustain a business model [23]. This data suggests low user stickiness, with many elderly reducing usage after the novelty wears off. As a result, user repurchase and recommendation rates for emotional companionship products are polarized: some users who benefit share their experiences in elderly circles, but many feel the products underdeliver and do not repurchase.

Social media and e-commerce platforms also reflect controversies. Many netizens (including younger generations) question whether companionship robots are “just a tech tax,” unable to truly replace human or pet companionship [24]. Some users who purchased robots noted stiff responses and unengaging conversations, leading to high idle rates [24][23]. Typical use cases include chatting when alone, playing music/operas, and simple reminder services: for example, some smart speakers greet the elderly morning and evening or remind them to take medication; some robots play traditional storytelling or operas during leisure time. Usage typically peaks during lonely periods, such as early mornings or after dinner until bedtime. Some elderly report that listening to a robot tell stories or perform comedy before bed alleviates emptiness, providing comfort with a voice in the home.

Typical Functional Entry Points and Service Scenarios

Emotional companionship products often integrate into elderly lives through familiar, beloved functions, gradually expanding service scenarios. Common entry points and use cases include:

Opera/Music as an Entry Point: Many elderly love listening to traditional operas or nostalgic songs. Smart speakers and companionship screens quickly capture interest by offering “play Peking opera/Yu opera” or “play nostalgic songs,” then guide users to use chatting or video call functions [22]. In the aforementioned nursing home case, elderly residents started with listening to Yu opera on smart screens and later learned to use them for family video calls [22]. Familiar opera content serves as a friendly entry, making the elderly feel the device “understands” their preferences.

Square Dance/Fitness Activity Scenarios: In communities, square dancing is a key entertainment and social activity for middle-aged and elderly people. Apps like Tangdou (Sugar Bean) entered the market with “learn to dance” as a practical entry point, offering dance videos and music tutorials [25]. Tangdou gained favor with community dance team leaders, who recommended the app to teammates, rapidly spreading among elderly users [26][27]. Within four years of its founding, Tangdou served over 200 million middle-aged and elderly users, organizing over 4,000 monthly online and offline square dance events with over 500,000 offline participants, showcasing the power of community spread [28]. Elderly users often share dance videos at dance sites, encouraging peers to download the app.

Family Communication Scenarios: Video calls are a vital way for many elderly to connect with their children. Many companionship products emphasize “one-click video” as a key feature. For example, some elderly-friendly tablets or smart cameras are primarily used for video chats with children or grandchildren living far away. Many elderly struggle with complex smartphones, but these simplified devices allow easy family connections [22]. Elderly with strong family video needs are willing to try these products, and successful video call experiences increase their acceptance of other device functions.

Health/Safety Service Scenarios: Some companionship robots enter elderly homes with health monitoring or emergency call features, supplemented by casual chat functions. For example, products offering 24-hour fall detection or voice-activated emergency calls address the practical safety concerns of solitary elderly, who are willing to install them for security. Beyond monitoring, these robots may chat briefly or remind the elderly to dress warmly, gradually becoming a “thoughtful assistant” rather than a cold device [29]. In this scenario, functional attributes (safety monitoring) serve as the entry point, with emotional attributes (companionship) as an added bonus.

“Gift-Giving” Scenarios: Notably, children purchasing companionship products as gifts for parents is a significant channel for market entry [30]. Many companies target holiday gift-giving, emphasizing “bringing companionship to parents” to appeal to adult children. For well-educated, affluent elderly families, products highlight emotional care with loving designs, such as cute pet shapes or voices calling “Mom and Dad” for chats, satisfying children’s filial piety [30]. For mass-market families, products emphasize practical features like emergency calls, location tracking, or anti-lost functions at affordable prices, highlighting peace of mind [30]. In gift scenarios, products enter elderly lives passively, and sustained use depends on whether they truly meet elderly needs and habits.

Overall, emotional companionship products attract elderly users through entertainment content or practical functions, gradually integrating into daily life to provide emotional care. For instance, “smart companionship machines” position themselves as “content + service entry points,” offering elderly university courses, leisure videos, wireless karaoke, voice chats, and one-click medical consultations [31]. Elderly may start using the device for operas or singing, then discover courses, news, or doctor consultations, deepening engagement. In community settings, once a few elderly find a product useful, they spread it through friends or dance groups, creating “silver-haired word-of-mouth” that drives broader adoption.

Psychological Motivations for Acceptance or Rejection

Elderly users’ acceptance or rejection of emotional companionship products involves complex psychological considerations, including dignity, autonomy, social willingness, and trust in technology.

Acceptance Motivations:

Alleviating Loneliness, Seeking Companionship: For long-term solitary or lonely elderly, having a responsive “object” nearby provides significant psychological comfort. Even knowing it’s a machine, human-machine interaction can alleviate loneliness [16]. Especially for widowed or empty-nest elderly, chatting with a smart speaker or listening to it sing is preferable to silence. Machine companionship makes them feel “there’s some liveliness at home,” fulfilling a real psychological need.

Reducing Dependence on Children, Maintaining Autonomy: Many elderly avoid troubling their busy children but fear being alone in emergencies. Companionship robots offer a compromise: they don’t require constant child presence but enable immediate help or family contact if needed [16][32]. For example, robots can notify families during falls while allowing casual chats without disturbing children. This balance of autonomy and assurance makes some elderly comfortable accepting such products. As experts note, if elderly choose robot companionship, it must meet their needs in some way [33].

Curiosity and Satisfaction from Learning New Things: Some younger-minded elderly (especially urban, early 60s, educated individuals) are curious about smart products and eager to try them. Using robots or smart speakers feels like keeping up with the times, providing a sense of achievement. Cute pet-shaped robots spark curiosity and affection, treated as “electronic pets” that bring joy during interaction.

Emotional Outlet and Psychological Comfort: For disabled or cognitively impaired elderly with limited real-world social interactions, machines serve as outlets for expression. Reports indicate that SoftBank’s Pepper robot in Japanese nursing homes helps reduce anxiety in cognitively impaired elderly by chatting and singing [34]. Robots don’t tire of repetitive questions or conversations, offering unconditional “companionship” that fulfills the elderly’s need to be heard.

Family Atmosphere and Filial Piety: When companionship products are thoughtful gifts from children, many elderly accept them willingly, respecting their children’s intentions. The product represents love and care, making elderly feel “my kids are with me” when using it. For example, a smart speaker that records dialogues allows parents to leave messages for children, creating a unique family interaction that encourages use.

Rejection Reasons:

Perception that Machines Cannot Replace Genuine Emotion: Many elderly resist interacting with “cold machines,” viewing it as self-deceptive comfort. Tech figure Kai-Fu Lee has questioned whether it’s cruel to let elderly chat with lifeless, emotionless robots [24]. Many elderly feel that no matter how smart, machines lack genuine care and are unwilling to entrust personal emotions to programs. They prefer real human companionship (children, friends, volunteers), and choosing robots feels like a sad, helpless symbol, leading to psychological rejection.

Self-Respect and “Refusal to Admit Aging”: Some elderly feel that using companionship robots signals “I’m lonely and need machine company,” which harms their dignity. Many “young-minded” elderly refuse to admit they need companionship, rejecting products with elderly care connotations. They see themselves as middle-aged and feel that using such products labels them as “lonely and helpless,” causing discomfort and avoidance.

Privacy and Autonomy Concerns: Products with monitoring features (e.g., location tracking, anti-lost functions, cameras) may cause discomfort, as elderly feel constantly watched, infringing on their privacy. Some worry that machines recording conversations or family details could lead to data leaks or misuse, making them hesitant to use devices with cameras or internet connectivity.

Technical Fear and Usage Difficulties: High-age or less-educated elderly may fear smart devices, finding them complex or struggling with voice recognition that fails to understand dialects, leading to frustrating interactions. Some complain that robots are “not on the same wavelength,” like asking for the date and getting a weather report, which quickly discourages use. Surveys note that current companionship robots have weak emotional interactions and focus on functionality, yet the most in-need high-age, disabled elderly have low payment willingness and ability [35]. Immature functionality and low payment willingness lead many elderly and families to adopt a wait-and-see approach.

Price Factors (Cost-Benefit Considerations): Emotional companionship products are often expensive, ranging from thousands to over 10,000 yuan. Many frugal elderly are reluctant to spend, thinking, “This money could buy supplements or hire a real companion” [35]. Hearing cases of robots becoming idle further reduces perceived value. High prices and questionable value make many elderly and their families cautious or outright dismissive of purchasing, especially without subsidies or significant price drops.

In summary, elderly acceptance of emotional companionship products often stems from emotional needs outweighing rational concerns, while rejection is due to inability to accept “machine companionship,” distrust, or discomfort. Community-active elderly, with richer social channels, show less interest in robot companionship, preferring human interactions [15]. In contrast, institutional or high-age solitary elderly, with limited social options, are more open to electronic companionship—provided the product is simple and genuinely useful. As technology and attitudes evolve, acceptance of emotional companionship products is expected to grow, but current psychological barriers require patient guidance and continuous product improvements to overcome.

Entertainment and Learning Products: Consumption Willingness and Usage

Elderly Interests and Demand Motivations

The life pursuits of contemporary Chinese elderly have shifted from basic living security to higher-level participatory and enjoyment-oriented needs. They are no longer content with “enjoying old age” passively but seek a vibrant “second life” [36]. Their interest motivations for entertainment and learning products include:

Strong Desire for Self-Enrichment: Many elderly wish to “learn and enjoy” post-retirement. In the information age, knowledge updates rapidly, and many fear falling behind, hoping to stay mentally active through new knowledge and skills [37]. Surveys show that combating loneliness, improving skills, and maintaining health are the top three motivations for elderly learning [38]. They study photography, editing, square dancing, or health courses for both interest and self-care or family care [38]. This drive for lifelong learning has fueled the rapid rise of the online elderly education market.

Dual Needs for Entertainment and Socialization: In leisure, elderly enjoy watching videos, listening to music/operas, practicing tai chi, or playing cards. Reports note that their primary online activities are watching videos, reading news/books, listening to music/operas, and social chatting [39]. Entertainment and socialization often intertwine: square dancing exercises the body and builds friendships, while karaoke entertains and fosters interactions. Through these activities, elderly find peer recognition and belonging, fulfilling needs to be “needed” and “acknowledged” [40]. Especially for empty-nest elderly, online interest communities offer emotional support and friendships, significantly reducing loneliness [41][40]. Entertainment and socialization are key pillars of their spiritual lives, driving adoption of digital products.

“Refusal to Accept Aging” Ambition: Today’s early 60s “new elderly,” often well-educated and financially secure, pursue spiritual fulfillment and self-realization [42]. With ample time and spending power, they seek “new selves, new identities,” refusing to age passively [42]. Thus, urban silver-haired individuals try youthful activities like short videos, mobile games, or even live-streaming sales. Surveys show that 50-somethings are sometimes more active than younger users in certain entertainment fields. On the Quanmin Kge platform, “post-70s” users (50s) have 1.6 times the online time of “post-95s” and spend 3.3 times more on karaoke equipment than post-2000s [43], reflecting a vibrant, era-embracing mindset driving deep engagement in online entertainment.

Health, Wellness, and Leisure Interests: Health maintenance is a practical need. Activities like tai chi, square dancing, or brisk walking serve as both recreation and wellness. Elderly have a strong need for wellness knowledge and skills to care for themselves [38]. Online courses on health, nutrition, and traditional Chinese medicine are popular, reflecting a “learn for use” motivation [38]. Traditional cultural interests like calligraphy or Peking opera also attract elderly, offering cultural enrichment and achievement. Whether for physical health (wellness, skills) or mental well-being (entertainment, socialization), elderly show strong, diverse interests in entertainment and learning products.

Market Usage Feedback and Behavioral Data

The “silver-haired entertainment” and “silver-haired education” markets have grown rapidly, with data showing rising elderly participation and consumption willingness in digital entertainment and online learning:

High Internet Entertainment Participation: According to QuestMobile, by the end of 2021, China had 118 million mobile netizens aged 60+, accounting for 11.5% of mobile netizens, with over half spending over 4 hours online daily [5]. Short videos are the top online entertainment scenario for elderly [44]. On Kuaishou, silver-haired users are highly active, with daily usage time leading major social media platforms [6]. Elderly not only consume content but also create and interact. Kuaishou data shows that short video production is among the top three online courses preferred by elderly in the past three months [38], breaking stereotypes as many enjoy learning to produce videos [45][38]. This enthusiasm has led platforms to recruit silver-haired users as product testers or elderly advisors [46] to better serve this growing group.

Rise and Evolution of Vertical Platforms like Square Dance/Karaoke: Taking square dance as an example, Tangdou was an early leader in silver-haired vertical entertainment platforms. From 2015-2018, Tangdou’s user base grew rapidly, surpassing 200 million by 2018, with over 50% being 55+ [47]. By 2019, its monthly active users reached 20 million [47]. Tangdou’s success lay in capitalizing on the elderly’s shift to mobile internet, focusing on square dance content to build sticky users and leveraging WeChat groups for viral spread [48]. However, competition is fierce: as Douyin and Kuaishou targeted elderly content, many square dance influencers shifted platforms, reducing Tangdou’s user base [49][50]. By August 2022, Tangdou’s silver-haired monthly active users were about 3.118 million, far below Douyin’s 7-9 million for prominent square dance accounts [51]. This shows elderly users vote with their feet, flocking to platforms with richer content and larger communities. While vertical apps saw explosive growth, long-term retention requires continuous innovation to maintain elderly loyalty [48].

Emerging Scale of Online Elderly Education: CNNIC data shows that over the past decade, netizens aged 50+ have grown steadily, reaching 350 million by the end of 2023 [3]. In the past three months, 23.3% of middle-aged and elderly netizens participated in various training courses, with 10.1% choosing online education and 5.1% paying for courses [52]. This translates to about 35 million elderly accessing online courses, with 17.85 million as paid learners [53]. While not yet mainstream, online elderly education has tens of millions of users. Promisingly, 34.6% of middle-aged and elderly netizens expressed willingness to participate in online learning, with 12.9% interested in purchasing three or more courses [53]. This reflects growing enthusiasm and potential. Consumption-wise, elderly online learners are “time-rich, financially secure, and willing.” Kuaishou reports that these users are often 50-59-year-old women in tier-2/3 cities with college education and monthly incomes above 5,000 yuan [54]. With independent children and light family burdens, they are willing to invest in self-improvement [54]. Some high-end users spend over 70,000 yuan annually on learning (including travel and study programs) [55], though most are pragmatic, with over 90% purchasing only 1-2 paid courses [53].

Typical Usage Periods and Frequency: With stable post-retirement schedules, elderly have ample, regular time for entertainment and learning products. They often follow a routine of morning exercise, daytime learning, and evening entertainment. For example, many start the morning with opera radio or square dance apps; post-lunch, they may attend an hour-long online calligraphy or health course; after evening square dancing, they browse short videos or news; and before bed, they watch a favorite opera video on a tablet. Data shows “Xiaoman group” (45-59 active netizens) average 127.2 hours monthly online, spending 2.8 hours daily on short video apps and applets [56]. Unlike youth active late at night, elderly peak during daytime and early evening, using clear-headed morning hours for learning and relaxing post-dinner. They prefer large-screen, large-font, simple devices to avoid eye strain or mental fatigue [57]. For example, Kugou Music’s “large-font version” app, optimized for elderly, has over 85% middle-aged and elderly users [57]. It offers clear fonts and integrated news and video content, extending elderly engagement time [57].

User Repurchase and Word-of-Mouth Spread: Elderly users’ spontaneous recommendations are prominent in entertainment and learning. Their “group-oriented” nature drives sharing of useful products. Kuaishou reports over 90% of elderly online learners discuss courses with friends, with 20.8% enrolling in classes together in the past three months, showing social fission [58]. For entertainment, word-of-mouth is evident: a good square dance app is recommended by dance team leaders to entire teams, or reliable live health programs are shared among friends. Due to fixed social circles, positive elderly word-of-mouth spreads faster and with greater stickiness than in youth markets. This is seen in Tangdou and WeChat mini-programs going viral or offline courses filling up via elderly referrals [48]. Reports note that elderly universities in China face “course shortages,” with many elderly enrolling in groups, highlighting word-of-mouth’s role in driving demand [59]. However, negative feedback is equally impactful—elderly warn each other about “scammy courses” or “overpriced apps,” quickly eroding poor products’ markets. Thus, silver-haired market repurchase and recommendation heavily depend on user experience and trust, with loyal elderly potentially offering higher lifetime value than younger users due to stability and deep hobby engagement.

Typical Functional Entry Points and Service Scenarios

Entertainment and learning products leverage familiar elderly interest scenarios for design and promotion. Below are typical entry points and service scenarios, and how these products integrate into elderly lives:

Square Dance Community Spread: Square dancing is a quintessential Chinese elderly entertainment scene, from urban parks to rural open spaces. Companies seized this, launching square dance teaching apps like Tangdou as entry points [25]. Functions provide vast dance video libraries and step-by-step tutorials, addressing elderly needs for “finding music, learning steps” [25]. Tangdou, the largest square dance video site in the PC era, transitioned to a mobile app in 2015, riding the elderly’s shift to mobile internet and gaining massive users [47]. It attracted dance team leaders who learned new dances and taught teammates, spreading the app [27]. Competitors like Jiuaiguangchangwu emerged, creating a vibrant silver-haired dance community [47]. Tangdou organized thousands of monthly online/offline dance competitions, enhancing user stickiness and pride [28]. This scenario meets entertainment needs and builds social platforms, creating a cycle: dancing → learning new dances via app → joining competitions → attracting more dancers → more app users. Though some users shifted to Douyin/Kuaishou, square dancing as an entry point proves elderly acceptance of digital entertainment when aligned with their interests [27].

Opera and Storytelling Content Services: Traditional opera is a beloved spiritual nourishment for the elderly. Companies launched opera apps or devices for “listening to opera.” For example, the “Xiqu Daguan Yuan” app, designed for elderly, offers Peking opera, Pingju, Yue opera, Huangmei opera, storytelling, and comedy, supporting voice requests and offline downloads for easy access [60]. Some smart speakers have built-in opera libraries, playing on command like “play Peking opera ‘Drunken Concubine’.” “Opera machines” (radio-like players) with preloaded operas are popular, with simple knob and play controls ideal for elderly unfamiliar with smartphones [61]. The entry point is opera/storytelling content they love. Once elderly start using these devices, they begin digitization—some opera apps offer square dance videos or health lectures, expanding usage [60]. Scenarios include elderly listening to opera for half an hour in the afternoon or evening, enjoying leisure without eye strain. CCTV notes that smart speakers, opera machines, and audiobooks are “boredom busters” for many elderly, with loud sound, easy operation, and eye-friendly design [62]. These services are used in homes and community cultural centers, where opera video players are common, supporting cultural aging.

Health Knowledge and Online Consultations: Health and wellness are critical elderly needs, with many care apps using this as an entry point for learning and services. Elderly universities or care platforms offer health and nutrition courses, attracting elderly learners [38]. Some companionship devices provide one-on-one online doctor consultations via video, addressing minor health concerns [31]. Scenarios include elderly checking dietary advice on an app after morning blood pressure checks, watching diabetes care videos at noon, interacting with instructors in comment sections, or joining live health lectures in the evening, learning simple exercises. Health content is an effective entry point, as elderly proactively learn for wellness. Trusting platforms with useful health knowledge, they explore other courses or communities, becoming sticky users. The National Open University’s online “elderly university” platform had millions of elderly learners by 2022, with nearly 70% accessing via smartphones, showing mobile devices as key carriers for elderly education and health info [63].

Online Karaoke and Gaming: Many elderly revive hobbies like singing, cards, or fishing post-retirement. Karaoke is highly popular online. Tencent’s Quanmin Kge data shows 50+ users as a mainstay, with post-70s leading in duets, messaging, and sharing, with high spending on gifts, rivaling younger groups [43]. Kugou’s “large-font version” app for elderly integrates karaoke, games, video duet calls, group voice chats, news, and short videos, meeting “one-stop” entertainment needs [57]. Scenarios include elderly singing a favorite old song, matched with a peer for a duet, then following each other to share recordings. This online karaoke experience builds new friendships, fulfilling talent display and social needs. In gaming, elderly-friendly mobile games or voice-enabled chess apps allow online matches without spatial limits. During the pandemic, many elderly learned to play mahjong or fight landlords on tablets, chatting via voice, maintaining fun. Entertainment apps with social features foster connections during play, serving as companionship.

Elderly Social and Learning Communities: Some products position as elderly social-learning platforms, offering square dance, photography, calligraphy circles, and courses, creating comprehensive communities. The “Xianqu Dao” app targets post-50s/60s/70s retirees, providing efficient social and entertainment services [64]. During the pandemic, it launched voice chat rooms for themed discussions, boosting user engagement [41]. Elderly discuss health, emotions, marriage, or retirement life, singing or playing voice games to bond [41]. The platform introduced real-time duet singing, meeting social-entertainment needs [65]. Entry points include interest groups and activities like photography contests, health Q&As, or online song meets, keeping elderly active. These virtual communities expand social and activity scopes for mobility-limited or homebound elderly, enabling friendships and learning.

In summary, entertainment and learning products succeed by aligning with elderly interests and activities, retaining users through community interaction and comprehensive services. Elderly entertainment and learning are closely tied to socialization, requiring products to offer content value and social bonds. For example, Tangdou gained traction with square dance content but retained users with community atmosphere and local events; Xianqu Dao retains users with chat rooms driven by shared interests. The “content + social” model is prevalent in silver-haired products. Different subgroups show preferences: urban elderly in tier-1/2 cities have high digital acceptance and payment ability, favoring comprehensive platforms [66][67], while tier-3/4 or rural elderly have lower digital engagement, relying on local community activities or TV/radio [66]. Thus, promotion varies: urban areas emphasize trendy online features, while rural areas combine offline elderly activity centers to promote apps, gradually increasing penetration.

Psychological Motivations for Acceptance or Rejection

Overall, most elderly have a positive attitude toward entertainment and learning products, readily accepting them if they align with interests and have low usage barriers. However, psychological factors influence participation or rejection:

Acceptance/Active Participation Motivations:

Achievement and Value Sense: Learning new knowledge or skills brings immense achievement. Many elderly initially doubt “I’m too old to learn,” but mastering a phone function, dance, or earning a course certificate fills them with pride, proving “I’m not worse than the young.” For example, a 65-year-old learning to make short videos and gaining hundreds of Douyin likes felt thrilled and motivated to continue [38][68]. This joy of recognition and rediscovering self drives elderly participation.

Enriching Life, Combating Boredom: Retirement offers ample time, but without hobbies, life can be monotonous. Entertainment and learning activities provide structure and purpose, making life meaningful. An elderly person may have vocal lessons on Monday, calligraphy on Wednesday, and square dance practice on weekends, keeping life engaging. Many say, “Since learning to watch operas online and chat with old classmates in groups, days pass quickly, not like before when I’d zone out” [62]. Eliminating emptiness and finding purpose are key reasons for embracing these products.

Social Belonging and Emotional Support: These products often come with social circles, offering belonging. Square dance teams, online interest groups, or elderly university classes form “mini-societies” where members encourage each other. For solitary elderly, these circles provide a “friend group” and peer support [40]. “At song meets, everyone praises my singing, and I feel great,” fulfilling social recognition needs. Helping peers, like teaching phone use, boosts value and positivity, enhancing mental well-being [40].

Continuing Life Roles and Interests: Many elderly embrace learning to continue past professional identities or dreams. A retired teacher teaching English at an elderly university regains purpose; a former art enthusiast picks up painting via online classes, fulfilling long-held wishes. These platforms offer a “fresh start,” letting elderly pursue unfinished interests or roles with enthusiasm.

Family Support and Social Advocacy: Children’s encouragement and technical help boost elderly confidence in using new products. Many learn WeChat or video calls with family guidance, expanding to other apps. A societal push for “active aging,” with media showcasing elderly models, dance contests, or silver-haired influencers, makes participation feel honorable, reducing psychological barriers and reinforcing adoption.

Rejection/Low Interest Motivations:

Technical Barriers and Fear: High-age or less-educated elderly, especially in their 70s-80s, fear digital products. Even simplified apps feel daunting if they struggle with basic smartphone use. Errors or complex steps like account registration discourage them. Some try but abandon due to unresolved technical issues, feeling “I can’t learn” or fearing breaking devices, keeping them from engaging despite interest.

Fraud and Safety Concerns: Frequent news of elderly online scams makes some overly cautious, especially with warnings from children to avoid online purchases or strangers. Some refuse apps beyond WeChat, fearing scam links, or avoid paid courses, worried about fraud. CCTV reported 69% of elderly phone users delayed sleep, and 44% reduced family communication due to overuse [69], raising family concerns about addiction or scams, deterring some from new entertainment.

Reliance on Traditional Methods: Decades-long habits favor traditional entertainment like TV, radio, or card games over digital alternatives. Elderly prefer in-person opera singing or face-to-face classes over online ones, finding screens less authentic. Especially in rural or high-age groups, low trust in apps reduces interest, as they prefer familiar, tangible interactions.

Psychological Barriers (Embarrassment/Self-Doubt): Some elderly are interested but held back by face or insecurity. A man may want to square dance but feel it’s “for women,” fearing ridicule; a low-literacy elderly may avoid computer classes, scared of looking foolish. Worries about being seen as “slow” by younger teachers also deter participation. Self-esteem and fear of embarrassment prevent some from trying, avoiding activities that might expose weaknesses.

Economic Considerations (Low Payment Willingness): Despite spending power, elderly are cautious with entertainment/learning expenses, prioritizing essentials or children. Spending thousands on premium courses feels extravagant, as “books or TV can teach the same.” Free or low-cost elderly university or community courses reduce the need for commercial platforms [70]. Subscription or paid knowledge models struggle, as elderly prefer free alternatives like YouTube dance videos, rejecting paid apps due to cost rather than lack of interest [71].

In summary, entertainment and learning products are more readily accepted as they align with elderly interests and social needs. Promotion must address psychological barriers: lowering technical thresholds, enhancing security and free trials, and respecting elderly dignity with positive, non-condescending marketing. Subgroup differences are notable: younger elderly (early 60s) are more open to new things, while high-age elderly (80+) may lack energy for complex activities, preferring simple entertainment like TV or radio. Urban elderly have more tech exposure and peer role models, boosting participation, while rural elderly face weaker tech environments, lowering engagement [66]. Institutional elderly, with organized activities like singing or crafts, have less exposure to commercial digital products unless introduced by facilities. As the nursing home smart screen case showed, elderly enthusiasm is high when products meet their needs [22], emphasizing the importance of tailored design.

Conclusion

China’s community-active and institutional care elderly show strong interest and growing consumption willingness for emotional companionship and entertainment learning products. Loneliness drives exploration of companionship products, while active aging fuels demand for entertainment and learning. Market feedback highlights both high usage/sharing success stories and challenges like low companionship robot stickiness and paid conversion hurdles. As products improve (more elderly-friendly, easier to use) and digital literacy rises, silver-haired consumption in these areas will grow. This not only shapes the vast “silver economy” but also impacts every elderly person’s later-life happiness. As the saying goes, machines support material life, but human care nurtures the spirit [72]—combining technology and humanity can truly meet the elderly’s diverse needs, ensuring a vibrant digital sunset.

References

This report draws on multiple authoritative surveys and media reports, including statistics from the Ministry of Civil Affairs and CNNIC, observations on the silver economy and care tech from Xinhua and People’s Daily [4][2], AgeClub and QuestMobile reports on elderly entertainment, socialization, and online education [53][43], and in-depth coverage from 21st Century Business Herald and CCTV on care robots and the “square dance economy” [23][27]. Behavioral and psychological analyses incorporate real user feedback and expert insights, such as Beijing Normal University’s companionship robot survey [23], Kuaishou’s “Xiaoman group” insights [54], and industry practitioner experiences [17][30]. These sources support the report’s analysis of elderly consumption willingness, interest preferences, and psychological motivations, aiming to guide practitioners and society in better serving the elderly, ensuring technology and care benefit every silver-haired individual.

[1] [4] [37] [70] Silver Economy Booms, Online Elderly Education May Usher in a Gold Rush

[2] [20] Xinhua Finance Observation: When Care Robots Knock

[3] [6] [36] [38] [45] [52] [53] [54] [56] [58] [68] Kuaishou Releases “Xiaoman Group” Online Education Report: 104M Users, Strong Elderly Spending Power

[5] [7] [27] [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [46] [57] [64] [65] [66] [67] [71] [72] Silver Economy in Entertainment Scenarios: Elderly User Profiles and Online Behavior

[8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [24] [30] [31] [32] [33] [35] Deep Dive: Midea/Panasonic Enter, Why Are Elderly Smart Companionship Products Hot, Addressing 42% Elderly Loneliness

[21] [22] Jining City Government Update: Liangshan County’s Digital Civil Affairs Turns “Aging” into “Enjoying Old Age”

[23] [34] 5.5M Care Worker Gap, “Electronic Grandchildren” in Nursing Homes, How Care Robots Support 300M Elderly

[25] Square Dance Arena Battles: Tangdou’s Strong Skills Yet Struggles in Elderly Market

[26] Tangdou: Seizing Square Dance Entry, Tapping Silver Economy

[28] Silver-Haired Social Revolution and Spiritual Breakthrough: Elderly Entertainment and Social Platform Study

[29] Companionship Robots Support Happy “Sunset Glow”

[39] Listening to Music, Learning Dance, Ordering Takeout, Booking Tickets, Playing Games: Silver-Haired Tribe Gets Savvier Online

[47] [48] [49] [50] [51] Silver Economy Case Study: Tangdou Square Dance Full Perspective Lifecycle Analysis

[55] 90% Elderly Choose Online Learning, Top Learners Spend Over 70,000 Yuan Yearly, New Opportunities in Silver Online Education

[59] Xinhua Finance Observation: Reflections on the “Study Tour” Boom

[60] Recommended Apps for Elderly Opera Listening

[61] [62] What Can Elderly Do Without Smartphones?

[63] Can Elderly Education Unlock Elderly Consumption

[69] Elderly Smartphone Addiction Linked to Higher Cardiovascular Risks

Comments